It's Really Not That Complicated

The Troubling Historiography of Indian Removal

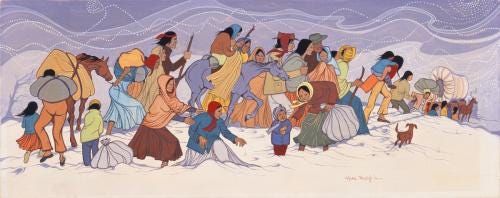

For my forthcoming biography of Martin Van Buren I have recently been writing about Indian removal, the expulsion of tens of thousands of Native Americans from their ancestral homeland in the 1830s. It’s a terrible story of dispossession, violence, greed, and conquest on a vast scale, and one of the great humanitarian crimes in US history.

The historiography on this subject is not pretty. Many of the classic books about Andrew Jackson and his times barely mentioned removal at all, and those that did were generally supportive of it. In Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Age of Jackson (1945), for example, he devoted exactly one sentence to removal.1

By the 1980s this omission was no longer permissible, but that didn’t improve matters a whole lot. Most historians tended to tell the story from Jackson’s perspective. Sad and tragic though it was, the line usually went, removal was necessary to ensure the safety and survival of America’s aboriginal peoples. Jackson meant well. He could be clumsy, even cruel, but his goal was to save the Indians from extinction, and this is what we should remember most before we condemn the Old Hero. “To his dying day on June 8, 1845, Andrew Jackson genuinely believed that what he had accomplished rescued these people from inevitable annihilation,” Jacksonian scholar Robert V. Remini wrote. “And although that statement sounds monstrous, and although no one in the modern world wishes to accept or believe it, that is exactly what he did.”2

No one? Oh, I can think of a few. One of them is H.W. Brands, the nation’s most prolific historian. He averages a book a year, and he covers a wide variety of subjects. He’s written biographies of Benjamin Franklin, Aaron Burr, Jackson, Ulysses S. Grant, Woodrow Wilson, Franklin Roosevelt, and Ronald Reagan—all in this century alone! I’ve riffled through a few of his books that pertain to my field of study. I find them superficial and lightweight, but I suppose that is to be expected when you bang out books at his pace. I don’t begrudge someone trying to make a living writing history books. Still, when fecundity comes at the expense of accuracy, he deserves to take some hits.

In Brands’s 2006 biography of Jackson, he gave a spirited defense of his removal policies. Eight years ago he summarized his position in this video.

“Jackson took the view that the struggle will … end with the dissolution, the annihilation of the Indians unless they move west,” Brands said, pounding the table for emphasis. “Even if Jackson had wanted to defend the Cherokees of Georgia, he couldn’t have done it,” he continued, “because there wasn’t a federal army to speak of, he would have had to get state militias to do it. . . . So Jackson’s policy was: For the good of the Indians, and for the good of the United States, they must move.” “I can’t say that Jackson was wrong,” he went on, and finished with a story of how a Cherokee man at a book signing in Oklahoma sheepishly told him that Jackson was his hero for removing his people west, out of harm’s way. “Like everything in history,” Brands concluded, “if you put this stuff in context, it gets more complicated.”

This is a truly awful synopsis. It’s glib, misleading, counterfactual. He parroted Jackson’s self-serving justifications for mass violence, ignored the Indians’ suffering, and skipped over the wider political and economic goals behind removal. He presented the issue as one great act of charity on Old Hickory’s part. Also, “there wasn’t a federal army to speak of”? Of course there was. That army was used to massacre Indians.3 And then he neatly tied it all together with a bow about how the Cherokees are now “thriving” in Oklahoma, thanks to Jackson. You want proof? A Cherokee man whispered this to him at a book signing. Who needs scholarship when you have juicy anecdotes like this?

There’s nothing original or interesting about Brands’s arguments. He was repeating what was the longtime historical consensus.4 But I was especially annoyed at how he summed it all up as “complicated.” This is a tactic people use when they’d rather glide over an issue than explain it properly. It’s complicated, folks. I hear this line many times when pundits go on television to discuss world events: Israel and Palestine, Russia and Ukraine, the United States and the world. It’s designed to obfuscate, to confuse, to crush our innate sense of justice.

Indian removal is really not that complicated. Sure, learning about this ugly chapter in US history requires effort—a task only made harder by the specious scholarship already cited—but one does not need a graduate degree to grasp the racism and exploitation behind a mass campaign to crush civilizations in the name of facilitating white settlement, expanding slavery and Big Cotton, and building political power.

Samuel Johnson said it best: “Intentions must be gathered from acts.” Why can’t historians heed this simple, great truism? Brands and his ilk should take a harder look at Jackson’s acts and not his words. Even if one were to accept the “vanishing Indians” premise, how does the cruel and monstrous way in which removal was carried out demonstrate benevolence on Jackson’s part?5

This is not some obscure academic quarrel. Distorting Indian removal matters. The pain from these policies is still felt in Indigenous communities today, and historians must honor that—accusations of “presentism” be damned.

Overall the state of scholarship on this subject has never been better. Jeffrey Ostler, Claudio Saunt, John P. Bowes, Nicole Eustace, Rebecca Goetz, Alan Taylor, Laurence M. Hauptman, and many others have done exceptional work on Indian removal. But too many historians, I believe, are still apt to side with the aggressors in this conflict. (And they tend to be the more prominent and visible historians, alas.) Don’t be quick to judge, we’re told. Our former leaders lived in different times. We know things that they didn’t. But their contemporaries judged them—and certainly their victims did as well. Their stories must be told, too. Even if that does make the narrative a little more complicated.

Good liberal that he was, Schlesinger later acknowledged his sins.

Remini, Andrew Jackson and his Indian Wars (Viking, 2001), 281. I should add that Remini’s book contains valuable research and insights, but I think his conclusions are dead wrong.

The administration claimed it was powerless to defend the Indians, but when it came to fighting them, the money and manpower were never in short supply. It would have been cheaper (and, of course, more humane) to enforce the Indians’ treaty rights than to remove them west. Jackson, it should be remembered, was ready to go to war with South Carolina over the principle that the federal government had the right to set and enforce tariff rates.

Brands is still peddling this line, by the way. See The Last Campaign: Sherman, Geronimo and the War for America (2022), 349.

Jeffrey Ostler dismantles the “vanishing Indian” theory in Surviving Genocide (Yale, 2019), 183-214.

I think you're correct that it's only recently that serious scholars have taken a more critical view of the Jacksonian belief in paternalism. The wikipedia entry on genocide still contains Wilentz's view, which itself is relying on Remini and Prucha. I'm anxious to get more into Ostler's take in Surviving Genocide. Just last night I read Appendix 1 of that book in which he summarizes some of the key issues and debates involved with using the term "genocide."