The Bloody References

My book is nearly done. Now comes the hard part: listing all my sources. Oh, can't you all just trust me?

Last month I discussed the life and work of Holmes Alexander, who wrote a dreadful biography of Martin Van Buren in the 1930s. Among the book’s many deficiencies (though the least of them) was its absence of sources. Alexander explained this decision in his book. “For the reader’s sake and my own, I have dispensed with footnotes,” he wrote, “and can only offer my word that all my quotations here are genuine, to the best of my knowledge.”

I don’t know which part of this is more rich—the claim that he was skipping this crucial part of the biographer’s job “for the reader’s sake” or his use of the “to the best of my knowledge” defense, which really gave him wide latitude, because his best wasn’t much at all.

Alexander is an easy target, but one of the great scholars of our time, the late Tony Judt, did something similar, though for different reasons, in his 2005 opus Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945. A masterpiece of narrative nonfiction, Postwar also came with no sources, not even a bibliography. Judt had an answer for this. “To avoid adding to what is already a very long book addressed to a general readership, a full apparatus of references is not provided here,” he wrote. “Instead, the sources for Postwar, together with a full bibliography, will in due course be available for consultation on the Remarque Institute website.”

He never quite got around to it. Few good things ever materialize once someone uses a phrase like “in due course.” He published a bibliography on the website, but we never got any notes. Judt’s omission cost him a Pulitzer. No sources, no prize, Stanford professor David M. Kennedy, who sat on the Pulitzer committee that year, reported. Judt had to settle for being a finalist.

Many of us still call them “footnotes” even though that’s typically not the right word. Footnotes, of course, are supposed to be at the bottom of the page. Today very few books have these. Outside Oxford’s History of the United States series, I can’t think of any off the top of my head. Considered stuffy, archaic, and a sure way to repel general readers, old-school footnotes are vanishing as quickly as the Latin terms that once adorned them: op. cit., loc. cit., passim, inf., sup.

I love footnotes and bemoan their coming extinction. It’s a great convenience to not have to riffle to the back of the book all the time to search for sources, a process Noel Coward once likened to “having to go downstairs to answer the door while in the midst of making love.” (Quite the analogy—now there was a man who loved to read.) How many treasures have I discovered because they were presented right there on the page, impossible for me to ignore?

Endnotes are in, brevity is out. Today one regularly finds in serious history books, even relatively short ones, appendices on sources well in excess of 100 pages—with smaller fonts, spacing, and margins, no less. Historians were once forced to be economical with footnotes; now they are free to list all sources (including tweets, emails, private conversations), expatiate on points they had originally wanted to make in the text, and, most entertaining of all, give us a juicy historiography scrap.

Scholars love poring over this stuff. Most are looking for material for their own studies, but many are also checking to see if the author’s done the homework. Too many secondary sources? No good. Relying extensively on one person’s diary or letters? Too limiting. On the other end, authors are eager to demonstrate that they’ve put in the requisite hours in the archives and, even better, traveled to far-flung places searching for new material.

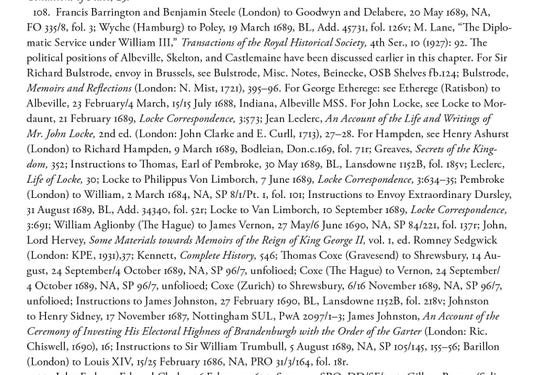

There is a performative element to the endnotes exercise. “Academicians use them as badges of erudition and scholarly one-upmanship,” Princeton’s Anthony Grafton once aptly put it. I suppose today’s “more is more” approach is preferable to the truncated Latin of yesteryear, but an abundance of detail has its disadvantages, too. Here is the endnote for a single (albeit long) paragraph in Steve Pincus’s magisterial 2011 book 1688: The First Modern Revolution.

I’m glad my field isn’t seventeenth-century Europe.

And now I’ve reached the stage in my book when I must get my sources in order. Time to show my cards. As I expected, it’s a slog. I misplaced key information on an 1802 letter, so I must return to the New-York Historical Society this summer—and I live in upstate New York now. There will be more of this, I fear.

Some of the work seems a bit unnecessary in the digital age, with so much available online and easy to find. Must I provide a source, for example, when I quote a president’s inaugural address? I guess I do, so here I am, looking up the pages in James D. Richardson’s A Compilations of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents, published in 1908, as if I’m still in graduate school. The art of sourcing has changed a great deal over the years, but thumbing through (or scanning over) old books will forever be part of it. Passim.