I’m a biographer of an obscure nineteenth-century president, which officially qualifies me as an eccentric, if not a crank. No, no, it’s all right. I accept society’s judgment.

But so was John Updike, one of America’s greatest novelists. So there.

Updike was not a biographer, but close. Since his childhood he was fascinated by James Buchanan, a Pennsylvania native like him. Buchanan was a spectacularly bad president. You will find him at or near the bottom of every presidents’ poll. Even now, as we all contend with the still-fresh nightmares of G.W. Bush and Trump, we must not forget Buchanan, whose wretched, bumbling four years in office led the nation to civil war.

Updike long held that Buchanan got a bad rap. Overwhelmed by forces outside his control, he did his best to stave off the coming carnage. We should pity him, not condemn him. So said Updike—and even a few historians. After all, he got his ideas from somewhere, that somewhere being the work of Philip S. Klein, whose 1962 biography of Buchanan, let’s just say, has not aged well.

Like Updike, I’ve long been fascinated by history’s losers. When I was a boy, I couldn’t read enough about Franklin Pierce. I’m sure I was the only 10-year-old in America who could tell you what the Gadsden Purchase was. I asked the local librarian in my small town if we carried a copy of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s campaign biography of Pierce (in which he wrote the immortal words “He is deep, deep, deep”). I wish I could recall her reaction. I’m sure there was plenty of giggling.

If any president’s life was marked by tragedy, it was “Handsome” Frank Pierce, whose good looks were a liability in antebellum America. All three of his sons died before reaching puberty, including the awful case of Benny, who was killed in a train accident months before Pierce took office. The story’s even worse than that. It was a relatively minor train accident. No other passenger suffered more than a scratch. But Benny—it’s still painful to write this—was crushed and nearly decapitated, right in front of his parents. Unimaginable.

Pierce’s wife, Jane, was so devastated she rarely left her room in the White House, always wore black, and said God killed her son so her husband could run the nation without distractions. She never climbed out of her doldrums (who could?), and neither did her husband, who resumed drinking. God’s plan for President Pierce backfired.

Now there’s some stellar material for a novelist, I say, but Updike (who was interested in Pierce as well) went elsewhere. I’m sure he grew up with stories about Buchanan and felt naturally inclined to defend Pennsylvania’s native son. But one is supposed to outgrow such attachments. Updike never did. He told Charlie Rose in 1992 that Buchanan “had been on my mind for most of my writing life.” Quite a thing to confess on television. Rose smiled and asked why. “He wasn’t such a bad guy, really,” Updike returned. “But I don’t want to bore you about Buchanan.”

Oh, bore away, John.

In 1973, at the height of his fame, Updike wrote a three-act play, Buchanan Dying. As the title suggests, it features Buchanan on his deathbed looking back on his expiring life. The play never got produced, though I’m unclear if that was ever Updike’s intention. The book was billed as “a play meant to be read,” but in his Rose interview Updike hinted that he was disappointed that it never got made. At any rate, I picked up a used copy years ago and found it enjoyable if preposterous. The ghosts of major figures from Buchanan’s past emerge to chat with him. One was Andrew Jackson, whom Updike transforms into a polished man with a rich vocabulary. “You tarried this morning,” Jackson says in one scene. (Tarried? The man had trouble spelling “the.”) Still, lots of good stuff: “There are no enemies in politics,” Buchanan says, “only potential allies.”

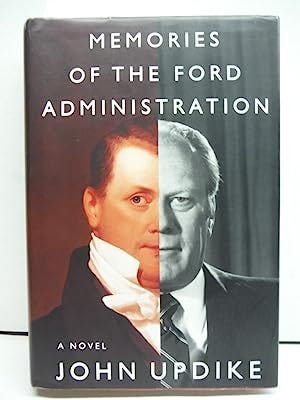

Twenty years later Updike wrote a Buchanan-themed novel, Memories of the Ford Administration. The book’s protagonist, Alfred “Alf” Clayton, is a philandering New England college professor and a Buchanan biographer who spends so much time in the archives that his marriage is falling apart. Alf’s attachment to his subject borders on the romantic. He describes Buchanan as a “big fellow, six feet tall, with mismatching eyes, a tilt to his head, and a stiffish courtliness that won my heart.” His wife tells him to give up Buchanan because he’s too dreary. “He’s not dreary,” Alf protests. “I love him.” Great line.

The book alternates between Clayton’s adventures and Buchanan’s. Since sex is the book’s main theme, Alf explores Buchanan’s tortured love life, most memorably his failed, tragic romance with Ann Coleman, who died of a broken heart when she learned that he was courting another woman. He also examines his close friendship with Alabama senator William Rufus DeVane King, the subject of much speculation then and now. “American gays, having seized as theirs Whitman, Melville, and Henry James,” Alf tells us, “among our crusty, straight-lipped Presidents must be satisfied with Buchanan, our only never-married chief executive …”

I recommend Updike’s books on Buchanan, even though the man was hopelessly sentimental about American history (Updike, not Buchanan). “I have feelings about presidents,” he told Rose. “I think they were all well-intentioned, honorable men. I don’t think there’s ever been a really evil president in the 40-odd we’ve had. They’ve all meant well.”

It’s no surprise that someone who held such views could fall in love with James Buchanan.