When the Left Was Laissez-Faire

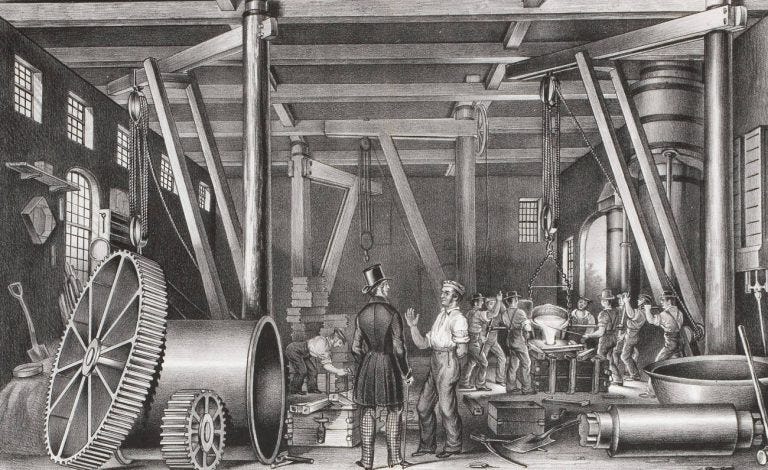

A primer on politics and organized labor in the 1830s

Last year—before you-know-who was elected president—I wrote the following essay for a left-wing publication, which either ignored it or didn’t think it was any good, because it never ran. Seemed like a waste not to share it with the world, so here it is.

In the 1830s America’s trade unions attacked the instruments of class warfare—banks, chartered corporations, paper money. Since those entities were creations of the state, opposition to government power was a central tenet of organized labor’s ideology. In other words, the militant elements of the class-based American left (a term not in wide use at the time) was militantly laissez-faire (ditto). Government intervention in the economy, these activists argued, led to inefficiency, cronyism, inflation, and favoritism of the rich and powerful. Only under a system of liberated free markets could the working man prosper. Milton Freidman wrote something similar in Capitalism and Freedom in 1962. Libertarians have been espousing such doctrines ever since.

Andrew Jackson’s election to the presidency in 1828 gave life to the nation’s nascent labor movement, then concentrated in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia. In left circles today, of course, Jackson is widely reviled for his role in brutally deracinating America’s Indigenous population east of the Mississippi River. But at the peak of his power Jackson was a hero to the white working class for his attacks on banks and corporations, especially in his successful campaign to defund the Bank of the United States, now known as “the Bank War.” Jackson’s supporters opposed the high-tariff policies of Henry Clay’s National Republican Party (later to become the Whigs), arguing that tariffs stifled trade and directed resources to dubious “internal improvements”—what people might mock today as “pork barrel spending.”

By the late 1830s radical trade unionists increasingly participated in the political system. They published newspapers, ran for office, and, of course, continued to organize and advocate on behalf of working people. Their unlikely hero was President Martin Van Buren, who won widespread union support for his call for a complete “divorce” between banking and government. (At the time, federal revenues were deposited in state banks.) They rallied behind his plan for a new “independent treasury” that would free the nation’s resources from banking’s more unstable practices, then widely seen as the cause of the Panic of 1837, one of the great financial catastrophes of the nineteenth century.

One of Van Buren’s key economic advisers was William M. Gouge, a bitter critic of paper money. “Some fancy that it is the authority of government that gives money its value,” Gouge argued in his popular 1833 manifesto, A Short History of Paper Money and Banking in the United States. “But the true value of money, as measured by the amount of goods for which it will honestly exchange, cannot be affected by edicts of princes or acts of parliament.” Gouge had a strong following among labor, especially those in the Workingman’s Party and the Loco Focos, a labor-based political movement that flourished in New York at the time. Other critics of centralized government included many of the day’s leading socialists, such as Robert Dale Owen, Thomas Skidmore, and Frances Wright. They argued for expanded suffrage, the ten-hour workday, abolition of imprisonment for debt, birth control, women’s rights, and universal public education. Many opposed slavery, though on the whole socialists were ambivalent (at best) about abolitionism. Such equivocating on the day’s great moral issues ultimately cost socialists the broader support they needed to counter the day’s power structure. Abolitionists found little use for any major party, especially Democrats, then generally pro-slavery.

Do antigovernment sentiments have any place today in left activism? After all, such standard socialist bugbears as empire and militarism are prime examples of rampant federal power. Can those unlikely alliances of yore see a resurgence in today’s politically fractured times?

Unlikely. An omnipotent Washington is problematic and even at times as sinister as its greatest critics insist, but governments, unlike private corporations, are at least nominally accountable to the public. The Freedom of Information Act still obligates public institutions to uphold some degree of transparency. Yes, the Pentagon is a mysterious, impenetrable beast, but state and local governments can be just as corrupt—and sometimes trickier to navigate, as many journalists can tell you. Balancing responsibilities among federal, state, and local governments is a thorny undertaking in a continental empire. Things were simpler when Jackson and Van Buren were in the White House. Even then, however, trade unions were misguided in their categorical support for the Democratic Party. The Erie Canal, for example, a project led entirely by the state of New York’s government (and opposed by Van Buren and his allies at first), facilitated more trade and prosperity than Gouge’s hypothetical theories ever could.

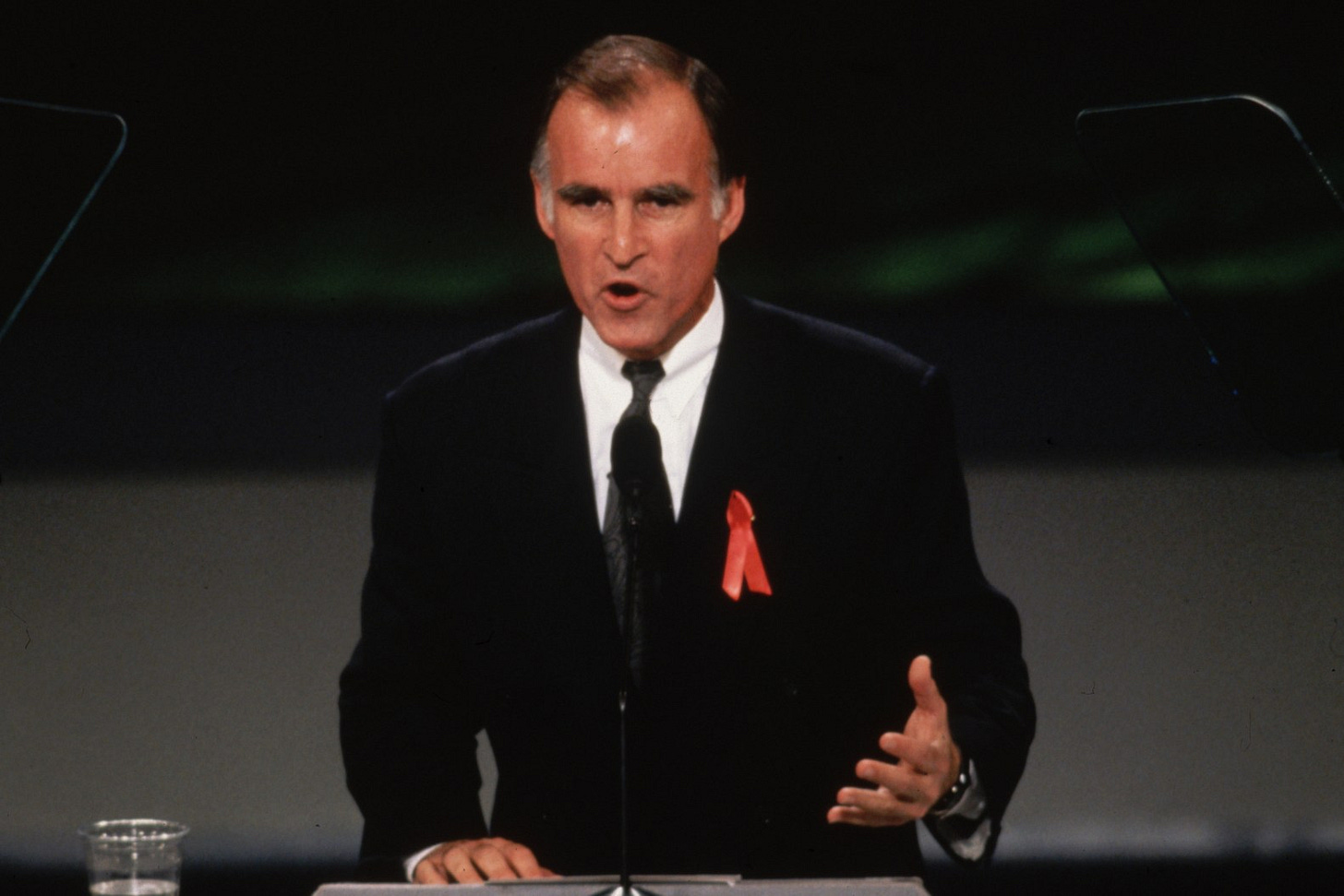

Lessons from the last time the left considered partnering with the libertarian right on the question of taxes and government are instructive. In his largely forgotten 1992 presidential run, former (and future) California governor Jerry Brown, in stark contrast to Bill Clinton’s business-friendly centrism, ran as a born-again radical. He deviated in one area, though. Befitting Brown’s eccentric nature (he was ridiculed as “Governor Moonbeam”), he advocated replacing Washington’s tax code with a 13 percent flat tax—a longtime dream of the Chicago school of economics. Brown cloaked his proposal in populist garb. By arguing for a simplified tax system, he said Americans could file their taxes on an index card and not waste money on accountants. He also called for the abolition of payroll taxes and gasoline taxes and for renters to receive the same treatment as homeowners in the tax code. That part of his plan received less attention. The big—and surprising—news was that a liberal Democrat called for a flat tax at a dramatically lower rate. The Wall Street Journal loved it. Soon thereafter, Republicans with eyes on the White House like Dick Armey and Steve Forbes (let’s not forget Hulk Hogan) made the flat tax the centerpiece of their presidential aspirations.

Brown urged progressives to give his proposals a closer look. Some did. In the Los Angeles Times, left-wing economist Robert Pollin saw merit in Brown’s plan “to eliminate the tax loopholes that favor the wealthy and the cabal of politicians, accountants, tax lawyers and lobbyists who feed off them.” Alexander Cockburn also clapped back. In The Nation, Christopher Hitchens wrote that the flat tax “offers something we on the left should always welcome: an opportunity to think about fundamental change. The plan has its flaws, some of them serious,” Hitchens continued. “But the intent—to clean the Augean stables of the present tax code, with its labyrinth of exemptions, exclusions and credits, producing a revenue loss at $393 billion, equal to the federal deficit—is entirely laudable.”

Nothing much ever came of the left’s brief flirtation with the Chicago school. Hitchens did court an unholy alliance with the right wing—not on tax rates, but on the War on Terror. (It didn’t end well.) On the subject of the national security state and its excesses, the libertarian right and peacenik left often find common ground, but not enough to have an impact in the electoral arena. As long as the left makes inequality central to its agenda—as it should—cooperation with the libertarian right will be as implausible now as it was between enslavers and union activists in the 1830s.