John Quincy Adams: A Man for the Whole People, by Randall Woods

The JQA train continues with a new doorstop biography

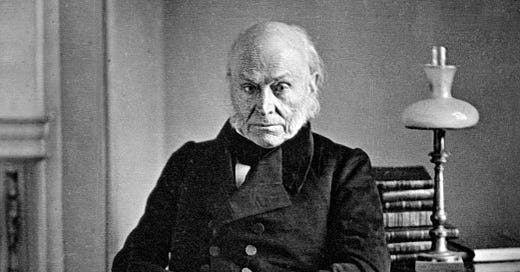

The past quarter century has been a fruitful and celebratory one for John Quincy Adams, sixth president of the United States (1825-29). On the heels of Anthony Hopkins’s hammy portrayal of Adams in the 1997 film Amistad1 came a flurry of laudatory biographies, most recently from Fred Kaplan, James Traub, and William J. Cooper. The Adams mania hardly ends there. In 2021 the Library of America published Adams’s abridged diaries (edited by David Waldstreicher), and we’ve even had two books about his wife Louisa Catherine Adams. And let’s not forget that Daniel Walker Howe practically made Adams the hero of his much-read, much-debated Pulitzer-winning 2007 study, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848. (Howe, in fact, dedicated his book to Adams.)

Does Adams really merit this level of saturation? Certainly he lived a long, important, and extraordinary life. He was John and Abigail Adams’s first (and by far most successful) son. As a boy he saw firsthand battles for independence. Highly educated and literate, he was a young diplomat in revolutionary Europe. He was secretary of state during the early days of westward expansion. He was a president and then a slavery-fighting crusader in the US Congress and a bitter critic of the Mexican War. There is much to plumb, nearly all of it illuminated in his remarkable Pepys-like diary spanning sixty-seven years. It is hardly a surprise, then, that his life has drawn the attention of so many admiring historians.

Into this crowded field steps Professor Randall Woods, who has written biographies of Lyndon Johnson and William Fulbright. His new book features the curious subtitle A Man for the Whole People. As Woods concedes, however, Adams harbored many of the day’s destructive prejudices against Native Americans. Adams was certainly not “for” them. He even advocated for their displacement—though not with the same intensity and ruthlessness as his successor, Andrew Jackson. As for the book itself, it’s as towering and sweeping as its subject’s intellect: 700 pages of text in small type and narrow margins. If you like your biographies on the meaty side, this one’s for you. I’m not a JQA expert, but A Man for the Whole People strikes me as the best and most comprehensive single-volume account of Adams’s life. (The best overall treatment, I would argue, remains Samuel Flagg Bemis’s magnificent two-volume biography published in 1949 and 1956.)

Accomplished historian that he is, Woods tells his story well. He knows how to write sentences, build a narrative, and supply the requisite facts and quotes. In recounting Adams’s personal life, Woods is especially strong. The chapter on his courting and marrying Louisa Catherine Johnson is excellent. He also offers powerful, heartbreaking accounts of the tragedies in JQA’s life, especially the deaths of his troubled sons George and John—both done in by alcohol and their own sense of inadequacy in a family whose standards were impossibly high.

Where Woods stumbles is in his coverage of politics. He fails to capture the day’s emerging party spirit and Adams’s inability to harness it. Instead he tends to see political battles as a contest between personalities: JQA vs. Jackson being the most prominent. Woods also relies too heavily on the diary—a common problem among JQA biographers. Common, but understandable: Adams’s quotidian observations, of course, are irresistible, offering rich, vivid accounts of the man and his times. Now the complete diary is available online—transcribed and in original form—ready for anyone’s perusal. The easy availability of such a splendid resource can work against scholars. If Adams were just a middling public official (like the real Pepys, for example), then a historian’s dependence on his diary would be justifiable. But he wasn’t; he heavily shaped—and was heavily shaped by—the times he lived in. To get a full grasp of this, one must look outside the diary and letters. Here is where Woods really falters.

In consulting the secondary literature for his study, Woods has turned extensively to Daniel Walker Howe’s two influential books, The Political Culture of the American Whigs (1984) and the aforementioned What Hath God Wrought, leaning heavily on the latter. Howe is an outstanding historian, but his work is often colored by a strident, visceral dislike for Jackson and the Democratic Party—a stridency matched by his admiration for Adams and the Whigs. There’s a wealth of scholarship deserving of Woods’s attention, and he appears to have ignored much of it. Nowhere in his bibliography or endnotes do I see references to the works of Sean Wilentz, Michael Holt, Charles Sellers, Alan Taylor, Steven Hahn, and Arthur Schlesinger Jr. How Woods could write a book about John Quincy Adams without consulting Holt’s seminal work on the Whig Party is especially puzzling. Woods, it seems, has similarly skipped over the excellent series from the University of Kansas Press on presidential elections, including Donald Ratcliffe’s superb study of the 1824 election—a central event in Adams’s political career. Had he read Ratcliffe’s book, he might have written a more thorough analysis of how Adams lost the popular vote in ’24. Woods (like Howe) chalks it up to the inflated power of the slaveocracy and the three-fifths clause in the Constitution. This is true, but Ratcliffe pointed out a more direct cause: New York, among other states, still awarded its electoral votes through the legislature, not the popular ballot. Had New York’s electorate had the opportunity to vote directly for president, Adams would have certainly won the state—and very possibly the national popular vote as well.

Despite these shortcomings, one must give Woods his due. He did yeoman’s work in writing this massive and often entertaining book. I suspect this is the last JQA biography we will see for awhile. If I’m right, that would be unfortunate. Despite the attention and praise Adams has recently received, much of it deserved, I still think there is more to examine—and criticize. Adams’s role in Indian removal deserves greater scrutiny. His push for continental expansion had fraught consequences—something Woods acknowledges but never really explores. His legacy is a mixed one.

Gore Vidal wrote at the time of the film’s release that Hopkins is “a solid, workmanlike English repertory actor, often excellent with a good English script like The Remains of the Day, often not so good if miscast, as in Nixon. But then it is always dispiriting that whenever a somewhat tony highbrow sort is to be impersonated, American producers, as vague about American class accents as about English ones, seize on British actors.”