On Pathography

Why are so many biographers harder on artists than they are on politicians?

In a New York Times book review in 1988, Joyce Carol Oates suggested a new term for a biography in which the subject comes off looking very, very bad: “pathography.”1 “Its motifs are dysfunction and disaster, illnesses and pratfalls, failed marriages and failed careers, alcoholism and breakdowns and outrageous conduct,” Oates wrote. “Its scenes are sensational, wallowing in squalor and foolishness; its dominant images are physical and deflating; its shrill theme is ‘failed promise’ if not outright ‘tragedy.’ ” I would just call it a hatchet job, but that’s why I’m no Joyce Carol Oates.

Though written thirty-five years ago, Oates’s essay remains relevant. Literary figures still often get rough treatment from their biographers. It’s a bit of a trademark of the genre.2 After all, if a biographer doesn’t deliver the dirt, what have you got? Hundreds of pages of literary criticism, and no one outside a few tenured professors wants that.

Oates disapproved of how pathographers “so mercilessly expose their subjects, so relentlessly catalogue their most private, vulnerable and least illuminating moments.” Amen, Joyce. I’d like to add another point to her argument. What does it say about our culture that books about gifted artists can be so scabrous while those about politicians—especially presidents—are just the opposite? What it says is that presidential worship, what Gore Vidal once called “that peculiarly American religion,” still runs strong, and that, in my view, isn’t a good thing.

Most presidential biographies are one long—often very long—eulogy. Exercises in myth and nostalgia, these books stress the importance of character and underplay the popular outside forces driving events. It’s bad history, even if some of these books make for good reading. (They sell for a reason.)

Perhaps the finest practitioner of modern hagiography was the late David McCullough, who earned fame and riches peddling feel-good Americana to the masses.3 McCullough was quite open about his desire to write only about people he admired. Spending time with a scoundrel bummed him out. He once tried to write about Pablo Picasso, for example, but found his subject so disagreeable that he scrapped the project altogether. “I didn’t like him—I didn’t like a lot of what he did and said,” McCullough said of Picasso in an interview. “He was a communist who was salting away millions of dollars in Swiss bank accounts, and he spent much of World War II worrying about his tomato plants. He was mean to his family and women.” Sounds like rich material for a biography to me, but McCullough had to follow his muse, of course. He wrote about Harry Truman instead and nabbed his first Pulitzer.

A pathography of a long-deceased statesmen is usually considered odd. The historian Garry Wills, for example, once wondered why anyone would take the time to write an unflattering biography of Timothy Pickering, a little-known diplomat from the powdered-wig era. “It puzzles me that some people spend their scholarly lives concentrating on a person they despise,” Wills wrote in his 2003 book Negro President: Jefferson and the Slave Power. “Perhaps that makes sense if the person is a great moral threat or scourge of history. . . . But Timothy Pickering?”4 (Interestingly, though, Wills gave Pickering lengthy and heroic treatment in his book. I guess “concentrating” on a forgotten politician is only puzzling when the author has nothing nice to say.)

Presidential pathographies are generally reserved for contemporary figures, especially the scandal-prone sort. It’s an easier task in today’s rabidly partisan times, when feelings are raw and contemporaries willing to dish. Before long, though, we are supposed to forgive the sins and remember the good. Again, a eulogy. Even George H.W. Bush can be apotheosized in his lifetime, provided Jon Meacham is on the case.

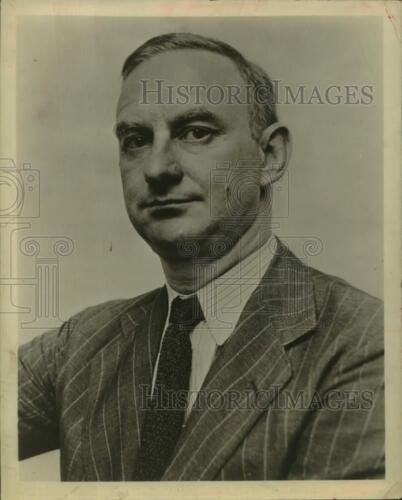

As it turns out, a pathographer once mugged my subject, Martin Van Buren. In 1935 a neophyte journalist named Holmes Alexander (above) wrote The American Talleyrand: The Career and Contemporaries of Martin Van Buren, Eighth President. In the annals of presidential biographies, few authors so intensely disliked their subjects as this one. His Van Buren was a villain right out of a bad Victorian novel: a fraud, a liar, a lout, a miser, a ruthless pursuer of power. Holmes could spin clever and funny sentences, I will grant him that; but The American Talleyrand is a contemptible book. Contemptible not because he despised Van Buren but because it has no scholarly value and is without any sense of scale, proportion, or nuance. It’s bizarre that someone writing in the mid-1930s could find Martin Van Buren a suitable target for such venom. Maybe Wills had a point.

So extreme was Alexander’s animus for Van Buren that it seemed personal. In a way, it was. Born in West Virginia in 1906, he was elected to the Maryland state assembly at the age of twenty-four and found the ordeal so soul-crushing that he soured on politics altogether. He wrote two well-received articles about his experiences for Harper’s. Literary agents came calling. It was suggested that he write a novel. By his own admission, he was terrible at it. Then he found his inspiration: Van Buren, the no-good knave who forever ruined politics by introducing patronage, legalism, euphemism, and double-talk to the practice of statecraft.5 Alexander went on to become a national political columnist of some renown. He also continued to write books, including biographies of Aaron Burr (unflattering) and Alexander Hamilton (highly flattering). I strongly doubt that any serious historian has or ever will profit from his work. He died in 1985.

Political biographers need not go to these extremes. One can portray politicians as interesting, complicated people (i.e., human) without excusing their misdeeds—and especially their crimes. History is not a struggle between good and evil. “So, Van Buren … good guy or bad guy?” I’m often asked. I cringe every time. It’s a terrible question—and the frequency with which it’s asked shows the dichotomous nature of today’s presidential narratives.

How do I reply to the “good guy/bad guy” question? “Both.”

Merriam-Webster’s online dictionary, however, says the term dates back to 1917.

Please note my use of the qualifier “a bit”: there are, of course, many outstanding literary biographies that don’t wallow in the lurid and the sensational.

I don’t wish to sound too harsh. McCullough was a fine writer, and some of his early books (e.g., The Great Bridge and The Path Between the Seas) are quite good. But his presidential biographies, in my view, are soft and sentimental.

Garry Wills, Negro President: Jefferson and the Slave Power (Houghton Mifflin Co., 2003), 18-19.

Alexander looked back on his experiences writing about Van Buren in his preface to his Hamilton book. See To Covet Honor: A Biography of Alexander Hamilton (Western Island, 1977), ix-x. Western Island, by the way, was the publishing arm of the John Birch Society.